At the end of this year, P&B chooses Uganda for its large annual zoom. This East African country has made great strides in the book industry in recent years. Exclusive conversation with a great figure of the country.

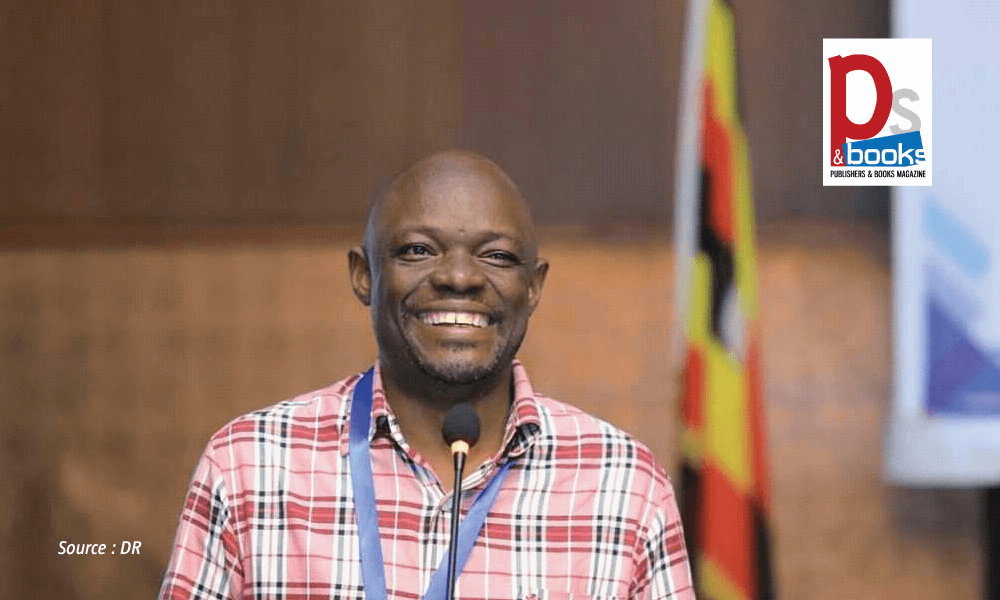

Publishers & Books: Already, if you had to introduce yourself to our readers, what should we learn?

Charles Batambuze: My name is Charles Batambuze. I am the Executive Director of the Uganda Reproduction Rights Organisation (URRO), a collecting society for writers and publishers of literary works in Uganda. I am also the Executive Secretary of the National Book Trust of Uganda (NABOTU) a non-profit, non-government umbrella organisation set up in 1997 to promote authorship, publishing and a culture of reading in Uganda. NABOTU is a private sector-led organisation that has for years now played the roles of a national book council especially in the area of book development. Prior to working with the above, two organisations, my first job was a Librarian at the then Public Libraries Board which later became the National Library of Uganda. I am highly involved in education and the creative sector as a member of several organisations like the Uganda Multilingual Education Network (UMLEN) advocating for mother tongue education; Uganda Library and Information Association and; the National Culture Forum.

P&B: You are a very active figure in the development of the book sector here in Uganda. You have therefore occupied the position of Executive Director of the national organization (URRO) in charge of copyright for almost 10 years. What is your daily job?

C. B.: On a day to day basis, my job involves planning, and execution of URRO Board decisions; supporting efforts and campaigns to recruit writers and publishers to sign mandates that give URRO the right to manage their copyright; license negotiations; taking part in copyright law awareness activities including regular posts on URRO’s social media pages and groups; ensuring that URRO meets its statutory obligations with the regulator (Uganda Registration Services Bureau); liaison with state agencies such as the Uganda Police, Customs and Courts that support URRO’s enforcement activities; partnership management and negotiation of reciprocal agreements.

What concrete strategies have been put in place to support and clean up the copyright protection environment in Uganda in recent years?

Firstly a supportive legislation, the Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Act 2006 and the Copyright and Neighbouring Rights Regulations 2010 providing for amongst others, collecting societies; copyright inspectors and other matters was a key milestone in laying the ground for proper copyright protection. Government has followed this up by licensing 3 collecting societies including URRO for literary works; UFMI for Audio-visual works and UPRS for musical works. The 3 licensed collecting societies under their forum, conduct joint activities such as copyright law awareness campaigns, advocacy for growing author royalties such as through private copy levy. The Uganda Registration Services Bureau (URSB) is the government agency responsible for the Copyright law, set up a Directorate of Intellectual Property of which Copyright is a key component and employs Copyright Registrars and other staff to support the implementation of the law. In 2017, URSB signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Inspector General of Police which resulted in the setting up of the URSB Enforcement Unit that provides support for anti-piracy activities as a result of which many criminal cases have been prosecuted. In 2019, the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP) licensed lawyers working at URSB as State Prosecutors to ensure that IP cases and specifically criminal cases of copyright infringement can be disposed off fast to avoid any backlog. At the level of URRO, some of our staff have been appointed as Copyright Inspectors with powers to search and confiscate infringing materials and gadgets. URRO introduced a hologram which was approved by URSB to be used on all books in the market. The hologram which has been fully embraced by all publishers operating in Uganda is used to authenticate books for the market, helps the Police and Copyright Inspectors in identifying pirated copies of books on the market and is used in courts as proof of infringement. Finally, URRO is offering a range of licenses including for education and public administration to enable education institutions, Ministries and agencies of government that use photocopying, scanning and digital copying to legally access such content at a fee which is used to remunerate rights holders as royalties.

How do writers across the country view copyright management? Do they regularly receive remuneration for the exploitation of their works?

A lot of awareness raising has been undertaken to help authors appreciate the value of collective management of copyright. It should be noted that collective management of copyright has been available to them since 2014 when URRO was licensed to work as a collecting society. In this short history, a majority of the authors laud our efforts of protecting primary markets for their books. We are now working on the secondary market for the right of reproduction. URRO has not done any distribution of royalties yet because it’s still in negotiations with users of works such as universities and public administration organisations on the framework license agreements. The key barriers to success have been the knowledge curve, which is, getting users to appreciate the need for authors to receive remunerations for works that are reproduced via photocopying, scanning and digital copying, and a culture of impunity evolved over many years of non-compliance with copyright laws. We have been telling users that taking up a license that enables them to legally exploit the works and paying for it, provides an incentive for authors to write more and guarantees sustainable local book industries.

A problem remains at the center of concerns in several professional forums: the management of copyright on digital content. How does Uganda deal with this particular point?

Indeed digital copyright management is a big challenge for Uganda. First of all in terms of legislation, there is a need to make our copyright law versatile by making adequate legal provisions for the digital environment. Government is currently working on the ratification of several International Copyright Treaties and later their domestication into law. Without the ratifications, it is difficult for Uganda content producers to benefit from digital markets, evolve adequate digital copyright management systems and benefit from reciprocal protection.

Secondly, as already noted, the 3 collecting societies have been advocating for the introduction of a private copy levy on all gadgets that can be used to reproduce copyright protected digital content. The levy would then be distributed as royalties to rights holders whose works are currently freely shared over digital platforms without authorisation.

Dear Charles, how do you become a publisher in Uganda? What is your assessment of the editorial landscape in Uganda?

Uganda is the most open country when it comes to entry as a publisher. There are no special rules for entry. All you need is to incorporate as a commercial or non-commercial entity or even just self-publish. However, a few laws you need to comply with after you have published your work such as the national deposit legislation requiring a publisher to deposit copies of their publications with deposit libraries at the National Library of Uganda, Makerere University Library and the National Documentation Centre at the Uganda Management Institute. The legal deposits help us to generate statistics on actual publishing outputs to enable planning for the book industry. Publishers are advised to secure the ISBN, ISSN and other numbers from the National Library of Uganda to facilitate local and international distribution of their works. And finally, publishers are advised to register their copyright, which is voluntary, at the Uganda Registration Services Bureau.

The publishing landscape is especially expanding the growth in numbers of indigenous publishing companies and outfits. At the moment, there is an interesting trend of especially young people, who because of limitations of traditional publishing, have set up new publishing platforms, most of them online, which provide outlets for their publishing activities. Educational policy, especially the use of local languages in education, has opened up immense publishing opportunities in 32 local languages and most recently the teaching of Kiswahili at all levels of education will add to this already positive momentum.

Professor Kenyan Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o called at the IPA seminar in Nairobi to promote editorial productions in African languages. What is your view on this question? Can we hope very soon for the birth of a real industry of books in national languages?

Yes. The rebirth of a real industry of books in national languages is already happening in countries in Africa that have adopted education policies that use and teach in African languages. It is the best thing to have happened in my view, to the development of African languages and the attendant literatures. In Uganda for example, the National Curriculum Development Centre (NCDC) has supported the development of orthographies for 32 African languages. This means that Ugandans are now writing books and doing text translations in those languages. These efforts are finally reshaping the publishing industry from the elitist mould to a more inclusive industry serving all language groups in Uganda. Otherwise in the past, the lack of books including for the general readership in the different local languages is responsible for making reading an elitist and marginalised activity.

You launched a call in September 2018 during Gustro Tertiary and Vocational Book Exhibition and Workshop. You drew attention to the tertiary book sector in Uganda. Why is it important for publishing professionals to explore this business sector more?

The tertiary level market segment has grown bigger and is projected to grow more. It mainly benefits the youth that constitute the largest portion of Uganda’s population. This youth dividend is responsible for increased enrolments to tertiary level education, expansion of the tertiary level sector and the attendant demand for books that support the various courses. Although the demand for tertiary level books is on the rise, there have been constraints such as the lack of local content books meaning that trainers and students have to rely on expensive foreign alternatives. We need to address this imbalance, and government of Uganda in 2018 called for publishers to write books for various courses for its vocational and technical colleges. We hope that this momentum drives publishing professionals in Uganda to continue producing appropriately priced books for this market segment to compete with foreign books.

Powered by ADEA (Association for the Development of Education in Africa) and other partners including the African Union, a framework agreement was approved by participants at the Nairobi conference last July. You were there. Can we say that Africa has taken an important step? Why?

There are countries in Africa without a local book publishing industry to write home about. There are also countries in Africa with a book publishing industry born out of necessity to support education but supported by sporadic procurement guidelines of the Ministries of Education which are heavily influenced by the World Bank and other donors. This publishing spectrum ensures that Africa lags behind other continents in the production of books and facilitates the growing dependence on book imports thus exacerbating information and other forms of inequalities. The African Union Continental Book Policy Framework as approved in Nairobi is for the first time getting African governments to commit to national book policies that will ensure budgets are made available for local book development activities in every country in Africa. This is a very important step that will in the coming years address inequalities in publishing and grow the influence, voices, culture and diversity of books by Africans in all spheres. The continental book policy framework in my view is therefore a pragmatic step towards regaining control of our thought processes, identity and destiny and sharing the same with the world.

Conversation with Ulrich Talla Wamba

Read the rest of the conversation by subscribing to the magazine now